The newest episode of our university podcast, ‘Mindful U at Naropa University,’ is out on iTunes, Stitcher, Fireside, and Spotify now! We are excited to announce this episode features special guests Anne Lamott and Neal Allen, author of Shapes of Truth: Discover God Inside You, exploring a contemplative method for discovering one’s inner nature that is influenced by Eastern traditions, especially Sufism and Buddhism, as well as contemporary psychodynamics. If you’re inspired to learn and grow and grow in your faith, be sure to explore our Master of Divinity program too!

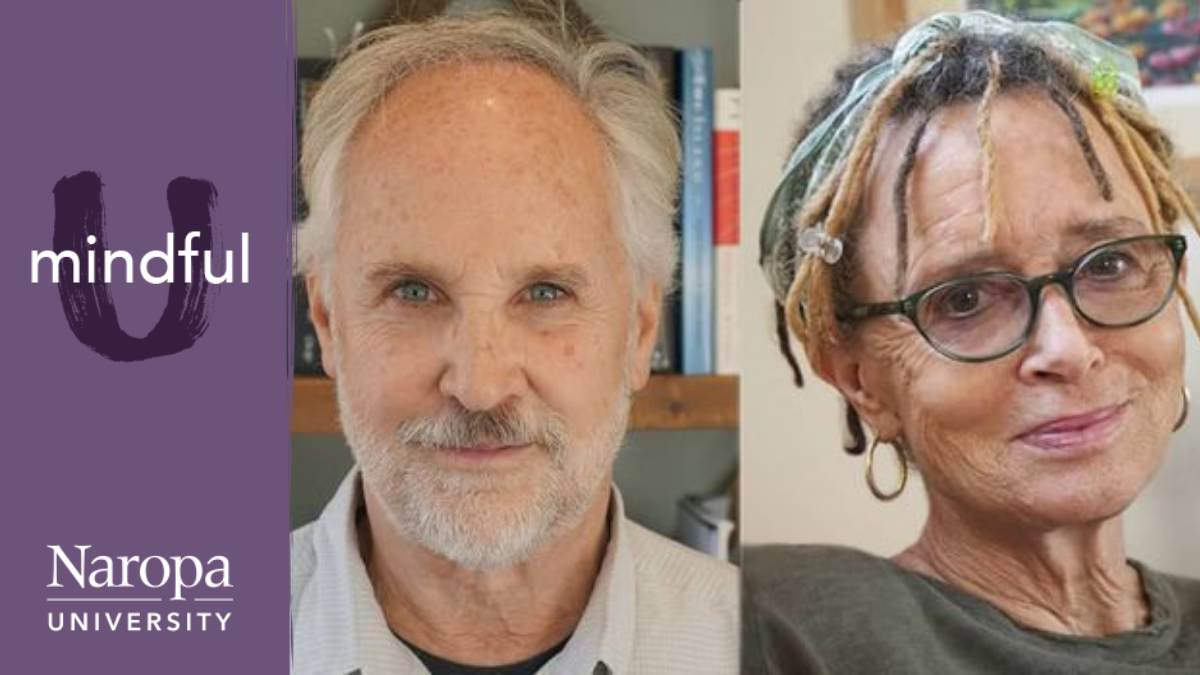

Anne Lamott and Neal Allen: Conversation for Shapes of Truth: Discover God Inside of You

Anne Lamott and Neal Allen: Conversation for Shapes of Truth: Discover God Inside of You

In this special conversation, spiritual coach and writer Neal Allen is joined in conversation by his wife, best-selling author Anne Lamott. Allen’s new book, Shapes of Truth: Discover God Inside You, provides a contemplative method for discovering one’s inner nature that is influenced by Eastern traditions, especially Sufism and Buddhism, as well as contemporary psychodynamics. Lamott’s best-selling spirituality books often explore a personal Christianity that is removed from the currently popular doctrinal evangelism. Together they discuss their collaborative writing life, practical approaches to spiritual practice, freedom from suffering, and much more.

Full transcript below.

About Neal Allen

About Anne Lamott

TRT 57 mins

[MUSIC]

Hello, and welcome to Mindful U at Naropa. A podcast presented by Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. I’m your host, David Devine. And it’s a pleasure to welcome you. Joining the best of Eastern and Western educational traditions — Naropa is the birthplace of the modern mindfulness movement.

[MUSIC]

[00:00:45.04]

DAVID:

Hello, everyone, and welcome back to Mindful U podcast. Before I introduce our special guests, I’d like to say it’s very exciting to be back and podcasting again. Mindful U has been on hiatus for a while, and now is back to share some space with our speakers and our friends. So with that today, I’d like to welcome our very special guest to the podcast, Neal Allen and Anne Lamott. Neal is a coach, a writer, a practitioner of spirituality. And Anne is a writer, a teacher, speaker, abductee to the California Hall of Fame, and an honored Guggenheim Fellowship Award winner. And of course, they are happily married to each other. Today, we are joined virtually with them who are fresh off speaking at Naropa University, from yesterday, about their book Shapes of Truth: Discover God Inside of You. I want to warmly thank them to the podcast. So how are you doing today?

[00:01:35.13]

Anne Lamott:

Good.

[00:01:36.12]

Neal Allen:

Good.

[00:01:36.12]

Anne Lamott:

We’re really happy to be here. And we loved being at Naropa last night, too.

[00:01:40.20]

Neal Allen:

Yeah. And are we happily married?

[00:01:43.09]

Anne Lamott:

Mostly.

[00:01:44.00]

Neal Allen:

Okay. I was — I’ll sign on to that.

[00:01:48.22]

DAVID:

He just had to check you on that real quick. So how did the event go last night? How was the Naropa crowd?

[00:01:54.13]

Anne Lamott:

Well, we’ve been mostly doing bookstores. And you know, several bookstores will join together to host us and so we’ve been talking about slightly more literary things and — and our marriage and reading from the book. And then Naropa, of course, was an opportunity for Neal to let his metaphysical freak flag fly so that he could — knowing that people read a lot of esoteric spiritual stuff that he could be much more esoteric than the book actually is. [00:02:23.14] The book is really pretty down to earth with this funny trippy thing — this discovery that we’ll talk to you about. But so he was so thrilled by the questions which were a little bit more esoteric than the ones we’ve been getting so far.

[00:02:38.07]

Neal Allen:

I got to use the word phenomenology. It was great.

[00:02:42.08]

DAVID:

Wow. Okay. Is there any other words you guys use that you’re excited about?

[00:02:46.17]

Neal Allen:

Well, the word metaphysics, I — oh, I used the term non dualism. I talked about four different forms of non dualism. I never get to talk about something called non dualism. I’m not sure I know what non dualism means or that anybody else knows. But I was allowed to pretend I knew what it meant.

[00:03:03.20]

DAVID:

Yeah. Well, I invite you to — to both be able to use those words and that vocabulary here.

[00:03:09.21]

Anne Lamott:

Thank you. I’m a Sunday school teacher. I don’t — I don’t go there anyway.

[00:03:15.02]

DAVID:

Awesome. So we have you on the podcast talking about your book, Shapes of Truth: Discover God Inside of You. And I’m curious, where did the inspiration come from to write this book and what ideologies guided you in the journey of writing this book?

[00:03:27.15]

Neal Allen:

You know, this book was actually given to me to write. So I had studied, in a mystery school, that’s based in both Boulder and Berkeley called Diamond Approach or Diamond Heart or it’s actually got three names, Ridhwan school. It is the brainchild and the functioning opening and teaching of a guy who writes as A.H. Almaas, whose real name is Hameed Ali. And I had been in the mystery school, which is a particularly efficient process of removing obstacles of the ego, which in the end is most of any self realization, or freedom or enlightenment path is getting yourself — your typical self out of the way. [00:04:11.22] And he’s got a really extraordinarily efficient way to do that. Efficient in this case means it takes six or seven years and I was a weekends — six weekends a year or two, eight day retreats a year. And so I did that and I — and I got on to his train, and I wrote it and traveled from station to station. [00:04:33.04] And it was spectacular for me. And I emerged trauma — with the sense of being rewired — and a different being, and a free being in a way that I hadn’t even known I wasn’t when I started it. But when I got out of it, I noticed that something had been bugging me for some time while I was in it, which was that a long among the other discoveries or teachings that he had brought to me, Hameed had brought me a teaching called the essential aspects. An idea that I am born with a direct perceived knowledge of aspects of God that I can conjure up as I need them in a kind of quasi physical way. I can see God as colors inside me. [00:05:24.19] And we’ll talk a little about it. Very trippy, right? I recognized when he first started teaching me this, like, you know, me, among other people in a classroom, right, or in a — in a hall. And sometimes he was teaching, sometimes one of his senior teachers was teaching, and I was just one of many. But one thing that I kept noticing was that these things reminded me of the platonic ideals and in particular, that Plato describes Socrates talking about in ancient Greece. And I thought that it was peculiar that 2500 years after Plato, there is a kind of further brand new discovery and argument for Plato having been right in a way that is slightly unbelievable. That we have an inborn wisdom, and Plato always said that and he said the inborn wisdom was — could be parsed. And my guess is — no way of knowing this, he had actually discovered these objects within himself — Plato or Socrates had. Who knows, because Plato basically cut off what he knew from being described. Saying that the mysteries — there were some traditionally illusion mysteries, but that he had discovered some additional mysteries himself and wasn’t going to share them. And he has his philosophical reasons for that. [00:06:46.21] Well, Hameed discovered these things. And they seem to have a bearing on the history of philosophy if they were really related directly to the platonic ideals. And so after I left Ridhwan school, I wrote Hameed and I told him, you know, the world doesn’t know that you’ve discovered this corner of Western philosophy — a platanus philosophy. You have it closed up within your mystery school as vocabulary that helps students reach Self Realization. But there’s also a more worldly and broader way that these can be known. [00:07:17.18] And Hameed wrote back, yeah, I think there’s a book there. And I could write that book. But I have other books that I want to write. And maybe if you write this book, I’ll help you. So I wrote the book. And the version of it was about Platonism. And it was erudite and somewhat academic, and well researched. And I got somewhat parsed by Hameed and reviewed, and at the back end of it from the start was a catalogue of these forms of characteristics of the God within that are accessible. [00:07:49.11] And it’s a kind of universal, metaphoric, symbolic vocabulary that we’re born with that is very easy to evoke. But the book changed as I approached publishers, and twice, I signed contracts with publishers, and each time I bought it back because they wanted to change the book a little more radically than I wanted to. And then I would buy back and I would kind of accept some of their change, but not quite as radical. And then the second time that I did it, I ended up saying, okay, I think I’ve now rewritten the book enough times that it’s readable, and that it’s less erudite and less philosophically based, and more of a, I hate to say this, but more of a self help book in the sense that it now plainly describes kind of useful method for giving your ability to see your inner value, your inner wisdom, your inner God, more cleanly to yourself, and that that’s a very useful tool for people, no matter what spiritual path they’re on. [00:08:50.10] So it gradually moved out of the Diamond approach logos and into a more generalized folky kind of book.

[00:08:58.05]

DAVID:

Yeah. Okay.

[00:09:00.02]

Neal Allen:

Did you have more of answer to that question?

[00:09:03.20]

DAVID:

I was resonating a lot with that. In some weird way, I was hearing divinely synesthesia, you know, it’s like finding the divine but experiencing it in multiple different ways. I also do feel like philosophy does equal self help.

[00:09:16.23]

Neal Allen:

Yeah.

[00:09:16.23]

DAVID:

You know, like, if you’re looking into philosophy, it’s questioning things. It’s discovering truths. So I do resonate with that.

[00:09:25.10]

Anne Lamott:

We haven’t been able to use the words divine kinesiology at any of our bookstore events.

[00:09:32.20]

DAVID:

Yeah, I’m all about it. We can get as trippy as we want. Honestly, like, I love that stuff. I’m a graduate of Naropa. So this is the content we produce here.

[00:09:40.23]

Anne Lamott:

Yeah.

[00:09:41.18]

Neal Allen:

Reminds me that I’ve been studying Eastern classics, more regularly for the last year. And one thing that’s come very plainly true to me is that when the thinkers and spiritual thinkers of ancient India and ancient China and ancient Japan were going about their pace and figuring out what to write about and what to tell people. And when Gautam Buddha was figuring out what to tell people, a lot of what they were doing was saying, you have a metaphysics built in and you don’t know it, you think you’re stuck with that metaphysics. And I’m going to disrupt that metaphysics for you for a little while and offer you a possibility that you could see life through a slightly different metaphysics. [00:10:24.22] And by doing that, you’re going to lighten up, right. And so one way of looking at everybody’s different view of non dualism, there’s a non dualism, where the material world and the empty world merge. There’s a non dualism where they overlay each other, but they don’t merge. There’s a non dualism, where you go all the way into the empty world, there’s a non dualism, that you go all the way into the mid — anyway, there are all sorts of — all they’re really doing is saying, take a different metaphysical viewpoint and try it on for a while and see whether it lightens you up.

[00:10:59.03]

DAVID:

Mm hmm. Yeah, finding different viewpoints sometimes can be hard. I sort of see it as like a pair of glasses, we wear over our heart, you know. So if like, we’re looking through our heart, it’s kind of like the lenses in which we look through. And sometimes we need to change our prescription. And sometimes we need to just clean our glasses, sometimes we need to take them off. So I love how you’re like speaking about that — of different ways we can look at things.

[00:11:24.10]

Neal Allen:

Anne you use that —

[00:11:25.11]

Anne Lamott:

I use that a lot too David. A priest to helped Bill Wilson get AAA off the ground, he was not himself an alcoholic, in 1935. And he said to Bill Wilson, sometimes I think that heaven is just a new pair of glasses. I think of that probably daily because I have the one pair of glasses that are kind of my natural, human clenching, grippy, judgmental pair and I see how much is wrong and how annoying other people are, and whatnot. [00:11:54.15] And then if I remember, it’s like, I can get spritzed out of that viewpoint, and put on the better pair of glasses. And then I just have a lot of wonder and a lot of love for everybody else. And even for my own very disappointing self. So —

[00:12:08.22]

DAVID:

Yeah, and I also have a saying where I say — consult the council. So we have like many different voices in our head. So it’s like, don’t just follow one of them. Because you got your ego, your heart, you got your mind, you got your little aliens and anunackies and like whatever you got up there, but consult the counsel, see what’s going on and then move forward with what you think is right. So it’s like, don’t just automatically decide sometimes,

[00:12:32.08]

Neal Allen:

The automatic decision is giving your super ego or your inner critic or your conscience authority to step in and answer too quickly. Right? Maybe the inner critic has, and the authority has a good idea. But hold on a second. There are other good ideas also possible in this and it’s interesting — I’ve noticed with my clients, most of my work with my clients is about taming their inner critic. And so I most work on objectifying the voice in your head, that it belittles you, and then finding ways — there are techniques in order to move it to the side so that it’s less active. [00:13:10.17] The inner critic is a particular voice in your head, or it’s actually slightly outside of your head, it’s not really coming from within. And once you’ve objectified it, you can notice that it is a relentless, continual narrator. And when you remove it or push it over to the side, a better narrator pops up. That is you. That is allowed to speak freely to you. And that usually has to like vie for attention with the inner critic. [00:13:43.03] And the inner critic usually wins by getting in the first — by rushing in and getting the first take on things. Simply noticing that I have an inner critic, and that it isn’t me. And that it — most of its power by jumping in right at the beginning, I can start to remind myself, I always have time to pause. [00:14:01.22] If it’s a social issue that I’m in conflict about or that I’m worried about or that I’m anxious about or that I’m this about or that about, then it isn’t survival. It isn’t about a snake or a stick. And I have time, and I can wait and pause and look around a little bit more before I make a decision.

[00:14:23.17]

DAVID:

Yeah, it almost seems like a good decision isn’t going to change between good and bad because you waited a little bit to make that decision. A good decision is always going to be good. Making a good decision is never a bad idea. It’s j like keep it simple, you know? So the word shape tends to come up a lot. I was wondering when you refer to the notion of a shape is it an actual image of a shape you visualize within yourself? Or does it hold more of a like a metaphoric symbolism, you know, speaking about the shape of holding something together. How does the word shape show up in this?

[00:14:59.18]

Neal Allen:

Yeah, all of the above. So this is the trippy part of the book is that the book describes a mechanical method in order to evoke a particular kind of shape with — inside you — inside you, inside me inside Anne. You know everybody has — has the capacity to do this. And shapes show up in almost the exact same way in everybody, it’s very odd that this hasn’t been known before because it’s so easy to do. [00:15:25.18] What happens is, I have an emotional difficulty, I’m thinking about the emotional difficulty instead of trying to fix it or avoid it or deny it or distract from it or do all the normal things that I do. Instead, I — I call a friend over and I close my eyes. And I ask my friend to ask me a few questions. And the questions are like this, is there anything localized in your torso or head or neck that feels a little tense or a little warm or a little cold? [00:15:54.11] I’m just looking for something that you notice inside yourself that is prominent and subtle, and sitting inside yourself. And then people will inevitably find something. It might be a little band of tension in the head, or often it’s a tension in the solar plexus, or it might be in the belly, or the neck or all sorts of places. The tricky part — and the interesting part, and the simple part is all I do next is said, now why does it? And by saying how wide is it, it stops being the name tension, it stops being the name for the emotional difficulty. It immediately and instantly — for everybody, it’s so weird becomes an actual thing inside. I don’t quite know how to explain this. You really have to do it to get it but in a kind of realistic and not unbelievable way, a little area is cleared out in my head or in my solar plexus or in my belly. And it’s as if I’ve hollowed out a little snow globe. And inside that snow globe is something that’s starting to emerge. So I say how wide is it? How tall is it? How thick is it? Now, I’ve got dimensions? What shape is it? Now I’ve got a sphere. I’m not — by the way, I’m not asking is it a sphere or a cube? I’m asking how wide is it? How tall is it? How thick is it? I’m gonna keep as — keep my hands off as much as possible, right? And then I asked how dense is it? And then all of a sudden the person negatively notices, well, it’s kind of airy, or it’s oh, I see it’s — it’s liquid? Or it’s rubber? Or it’s wood or it’s metal? Okay, is it shiny on the outside? Or is it mad on the outside? It’s kind of matte, okay, is it the same substance? Does it have a skin or is it solid, it’s all the same. And eventually, there is a completely described physical object sitting inside the body that is completely believable as a thing. And then I just tell the person look at it, explore it, now — you know, go inside it. And it turns out, I can become a little me and go into the center of it and look at it from inside out for a while and it’ll be dark in there. And I might see a little light shining. And after a while it’ll change. And usually this first object, when it changes either turns into a tube running through my body or it dissipates or it I throw it up it comes rising up through my mouth. And the first object usually represents — and I don’t even have to know anything about it. I might call it metaphorical. I don’t have to know what the metaphor means. And I just look at the thing and it rises out and it disappears. And that all feels very normal. And then I have like this empty torso for a while that’s dark, or might be a color in some vague way. [00:18:42.00] And then after a few minutes, I’ll ask the person, so what do you see now? And they’ll usually say nothing, oh, wait a minute, there’s a yellow thing here or a red thing here. That second object that shows up turns out to be who I am in support of myself for that emotional issue that I thought I had. And that I am actually full of the string, which is red or the will — white, or the curiosity, which is yellow. I thought I would — I didn’t have inside me. And I discovered that not only is the outside world perfectly capable of supporting me, my inside world is actually a very supportive machine.

[00:19:26.06]

Anne Lamott:

Yeah, I wanted to add a couple things. One is that there’s a catalog at the end — at the back of Shapes of Truth, it really tells you what every color, every shape and color mean and spiritually or in terms of there being a divine property. And so you don’t have to remember anything. And my case is good. And I wish the whole world was like that — that there was a catalog at the end of the book that told me what was going on. But and the other thing is, I wrote the foreword for this book and description, on our first date, I was feeling stressed out for a reason you can read about, but I was feeling just tense and it was our first date. So I was like, tense squared, right? And he said, do you want to do this funny thing I do with clients. And we did it. And so my first experience, the first shape I identified was not a shape so much as sort of a spill or a stain on the bottom of my tummy that had dimension. [00:20:29.12] It was like mercury. So it had — it was 3D. And it was a color I happen to hate, which was a brownish gray. And — but it was like a self contained puddle. But you know, sort of fractal in a puddle and — and little by little, and it was like the last thing I wanted to experience because as I said, I hate the color mostly because I look bad in it. I tend to like colors, and I look good. [00:20:52.06] So and he’d say okay — so how — how big is it? You know, how long is it? Oh, it’s about four inches long, I think. Is it deep? Oh, it’s a couple inches deep. And is it — oh, let’s just — what’s going on. And it was just a matter of him, teaching me the blessing of curiosity and patience. [00:21:09.09] And so he did — which is attention really. And so we did curiosity and his patience — and it was shifting, it was moving it was turning a slightly different color. And then it began to rise. And when I’ve watched him do this work with other people, it’s so simple. It’s being with somebody, your best friend, your mate, your kid who will sit there and every so often ask you a question about what the shape is doing. The shape will inevitably change into a different shape, which is in the catalog in the back. But for me this ugliest, you know, stain, this mercury dense stain turned into white balloon, and the white balloon rose out of me. [00:21:47.18] And it hovered beside me like in the Red Balloon movie, you know, as if by a string. And then it was on its own. And Neal said, oh, you went directly to the pearl. And the pearl is a very core our shape because it’s the soul. And so it went from this ugly tense thing — I had to let my assistant go and I cared for her but it wasn’t working out. [00:22:09.12] And I felt guilty and bad and mad. And — and it went from that to finding inside of myself that the shape of truth was my soul. You know, tell you another funny story. We had a book party for Neal on Sunday — on Memorial Day and — and I wanted to get him a cake that said Shapes of Truth. So I went to Safeway, where all great cakes begin, but the usual person wasn’t there. And the person taking the order didn’t hardly speak any English. So I could write down Shapes of Truth. And then I tried to explain that I wanted it decorated with various shapes. [00:22:43.22] And I’d say triangles and she didn’t know that and stars. And she was very, very sweet. But we were — I was trying to pantomime shapes. And then finally I said hearts and she said si, si hearts and she described him with her hands. And I thought that’s what the shape of truth is — the shape of truth is a heart. And so we got a cake, more like a Valentine’s cake, thinking reds hearts.

[00:23:11.22]

DAVID:

Yeah, the heart is a very important shape for sure. So I’m hearing this sense of, you know, if we have pain or trauma within, we love to put it over there or not deal with it or not confront it. And when we have the ability to confront it, then it almost feels a lot easier with us because we’re like, okay, well, I’m willing — it’s like that email that you keep putting off oh I’ll get back to it next week. I’ll get — and then it’s like — it’s just too late, you know, or like you’re trying to contact a friend. But it’s like when you have pain inside you. And you don’t want to deal with it, it festers a bit. But if you are able to be like alright, I have to deal with this and be emotionally mature and show up. And then you do — then there’s an ability of it just feeling at ease right away. But it’s still like an issue that you have to deal with.

[00:23:57.12]

Neal Allen:

This goes to the heart of why do I need these kind of structures inside of me — symbolic or metaphorical, but quasi real structures to be teaching me something inside when I’ve got words right? That the red sphere is very well represented similarly by the word strength or the word discernment, right, strength and discernment are kind of the same thing. Or a white mountain in my — why do I need a white mountain in my valley, if I’ve got the word steadfastness or will, right, that should be good enough. The problem with the words is we use them all the time. And so we have opinions about them. And so we have a — I have an opinion that if I hear the word strength, well I’m not really very strong. I’m not you know, I have to fake being strong because I know people who are really strong or discern things well, whatever I’m — I’m worried about. And so now, strength is colored by weakness and discernment is colored by fuzziness or steadfastness is colored by procrastination and I can’t keep them from appearing. [00:25:09.08] And I’m activating my super ego as soon as I hear the word strength to go — come in and say, no, you’re weak, you know, to start belittling me. So there’s something wrong with language in the sense that it doesn’t contain the purity of a word, the word tends to get contaminated by its associations. [00:25:28.08] And our — we all know that about our mind, right? We all know that it’s fairly unreliable in its most familiar way — that it can tell us — it always is participating in the truth in a broad way, right? Nothing falls outside of true nature, but at the same time, in a very narrow way, in my own life, I can be misguided by my mind. Now, my body is a little different, right? Because my body actually doesn’t normally have a capacity to lie. All it does is develop for a while and then maintain, right, and that’s its job — is to develop and then maintain, and it maintains accurately, and it’s going around fixing things all the time, you know, all these little 37 trillion cells fixing things. [00:26:13.05] And it only really knows how to operate accurately, and it’s trying to be as accurate as possible. So that might be a good repository for a different vocabulary. And there are a lot of people out there who have a sense that their body talks to them, right, and that it is more reliable. And that it has — there are people who find a way to evoke a kind of subtle word like vocabulary, it isn’t words, but it’s like words — well, this is associated with that, right? It has that kind of truth to it. [00:26:44.22] And what I find is, if I’m moving into studying an emotional issue, through my body, my body isn’t trying to convince me in any way that I’m not doing something interesting or important, right? If I’m listening to my mind, say words like oh you’re weak, you’re gonna get in trouble with the boss, if you do this, again, because you’ve always gotten in trouble, because you’re not very good at doing this sort of thing, then I’m smart to try to, like move away from that and not hear it. [00:27:17.09] But if — if I see it in myself as a benign object, that’s just kind of a brown puddle sitting at the bottom of my — well, I can kind of stick with it. And it’s kind of interesting. And particularly if I’ve done it a few times, I know it will disappear. It disappears oddly enough, I have this way of thinking about it that isn’t — clearly isn’t absolute truth in any sort of way, but gives the attitude right, which is when it feels like it has been fully seen for itself, this representation of my belief and my emotional conflict, waves goodbye, says thanks, you watched all the way through and now you have the right to see through me. [00:27:55.08] And then by the way, even before a divine object comes up, when that first object that represents the truth of the belief that I have an emotional issue dissipates or disappears from me, I fought every one of my clients and myself in doing this — I fall into exactly the state of being that Buddhists call equanimity. That state of contentment and self satisfaction that needs nothing at the moment. I don’t just get respite from my emotional issue that I happen to be looking at. I got respite from everything for you know a matter of minutes or hours, or it might stretch a little longer. And the more times I do it, or the more often that kind of respite can enter into it. Because eventually once I’ve done this 20, 30, 100 times it varies from person to person. I start to believe oh, that’s who I am. I’m not the voice up in my head. I’m actually this collection of body objects that’s — neither is who I actually am. But this one is telling the truth all the time. And it’s actually more accurate.

[00:29:01.07]

Anne Lamott:

Yeah, I mean, every single thing in me wants to just change channels when I have a clenched fist in my solar plexus or — or wherever — everything in me. I mean, that’s the American way, right? Is mood alter, you know, and run — run for your life. And that’s how I was raised. And every single thing I’ve learned or begun to embody or exude, that is precious and lovely came from someone helping me stay in the clenched fist, or in the ugly mercury spill in the bottom of my tummy. [00:29:39.17] And so that is radical. I mean, typically, certainly the first half of my life I got sober exactly halfway through my life. And the first half of my life basically, people would hand me nice bumper stickers of advice on how not to feel the exact way I was feeling. And then after I got sober — when I was 32, people started saying that the scary feeling or the uptight feeling — the despair, the dark night of the soul was actually the way home. And that if I could stay with it and breathe through it — it’s like labor, you know, it’s like the — each contraction tells you it will never end. And then you remember that you don’t actually like children. But then if somebody is sitting with you, and gives you a tiny sip of apple juice, and reminds you to keep your eye on the prize, then you bear it, because it’s giving birth to something new, that is going to blow your mind. [00:30:33.13] And so for 35 years, and the last five, especially with Neal, I have had the grace teaching, of staying with the miserable and the uncomfortable because it was — it is inside me, and it is going to teach me — it is going to heal me. It is at the end of the work gonna make me laugh. And I can tell you that with every single person I’ve ever seen Neal do the Shapes of Truth work, including myself, everyone just laughs — they go for Pete’s sake, because that was there all along and everything in them told them to run for their lives.

[00:31:11.21]

DAVID:

Okay, yeah, and we tend to have these dark nights of our souls every now and again. And I really resonate what you were saying of sticking with it — it feels like a rite of passage, emotional rites of passage, if we can push through the darkness and then try to find the light at the other end. And — and also, Neal, kind of what you were saying, we have all these voices in our head. And it’s like really hard to translate them sometimes. But what I’m starting to realize is, we aren’t the voices in our head, we are how we act upon them. So we are the filter between how we act and what we hear in our head. And the maturity comes in with how we display our actions and how — you know, like something bad could happen. And I could have all these voices telling me like, oh, you should do this, you should do that. And then I have my compassionate voices. And then I compile them together. And then how I act is who I am — not the voices in my head are who am I. So I was really digging on that.

[00:32:08.18]

Neal Allen:

Yeah, and it’s interesting you brought, you snuck the word compassion in there.

[00:32:13.07]

DAVID:

Oh, sorry about that.

[00:32:15.23]

Neal Allen:

The word compassion is really important to this kind of work, because the — probably the great gift that I found in meeting and falling in love with and joining lives in a way with Anne is that she has a comfort zone in a day of compassion, right? A lot of people — most people think compassion is something that you need episodically, right, and every once in a while, you need to be compassionate for somebody and they kind of conflate it with pity or sympathy or something else. And they think that it’s a useful tool. And it shows that you’re to be respected as a human being and taken seriously. Because when the chips are down, you can be compassionate. [00:32:59.16] And what Anne and I think I gone through life a little bit, this way too — notice is — is that most of the love that we bring into the world or notice in the world, from day to day and hour to hour is the love of compassion and compassion is the love that arises in the presence of suffering. [00:33:21.11] And most people most of the time in a completely non Buddhist way, are suffering. And they are talking — they’re complaining. If they’re talking to me — if they’re gossiping, they’re complaining and venting, and complaining and venting is the magical, socially acceptable, up to a point, way of bringing compassion — evoking compassion into the world. It’s basically saying I’m suffering and Anne is not scared of that and Anne is not scared of being — noticing that all the time and — and it allows you know it’s talking a little bit more about relationship the metaphysics here, but they crossover — is that if I can be open to the idea that suffering needs to be exposed in order to remove itself, and thank you for having seen it and allow a new free moment to appear without that suffering, then maybe I should be spending more of my life doing that. And Anne learned that kind of courageous way of life through suffering a long time ago, and I’ve learned it more recently. I just feel very lucky to be around — around her.

[00:34:31.12]

Anne Lamott:

There’s an excerpt from Shapes of Truth that Spirituality and Health.com the magazine, but it’s online if you want to read — it’s a compassion piece, because yeah, I mean, it’s everything that anybody listening is probably — has experienced as the shape of truth — as the kind of the symptom of healing that our hearts become softer — compassion is like meat tenderizer, you know, it just makes your heart softer, and bigger and warmer and more generous. [00:35:00.11] And then that is A) what heaven will be like — have a warmer, open — more open heart. And it’s also what will heal the world. So it’s huge to both of us. And I know that to you, David, and to everyone listening.

[00:35:13.18]

DAVID:

Amen. Thanks for that. Yeah. And I feel like there’s a sense of being witnessed is sort of healing as well. So when people are venting, when people are — they’re describing something, they feel heard, they feel witnessed. And so it’s like taking a load off, you know, it’s releasing some pressure off of them.

[00:35:32.04]

Neal Allen:

It’s very difficult to be a human being in an industrialized civilization. And mostly, what’s difficult about it is that I live next door to strangers. None of us, not one of us who doesn’t live in the deep Amazon or New Guinea lives in a human natural tribe, right? Where everybody around you on any particular day, the 200 people or less around you, on any particular day, are all completely 100% trustworthy. There isn’t an issue of distrust, until another tribe appears on that odd, you know, year when there’s a war or something like. That the — we live with a default of distrust, and it causes all of our problems. Because we have to defend ourselves, we have to build hierarchies. And there’s no way to go back. We do these silly things of developing particular kinds of identities in order to form a fake tribe. [00:36:30.12] And don’t notice that every time we want to form one of these fake tribes of identities, that we’re actually less joining a few people, then we are separating ourselves from almost everybody. [00:36:43.19] And it’s a very thorny problem. And that thorny problem makes most people suffer a great deal every day and think that things are going wrong, a great deal every day and — and that they have to hold up the whole system, a great deal every day. [00:37:02.04] And these objects inside remind me that I have a me who isn’t full of identities, and that me usually is described, you know, as a ineffable I am if you’re a (?) fan, or if you’re an (?) fan, as I am that and there are different ways of getting to that — that uncharacterizable me. What’s odd about this discovery of Hameed Ali’s is that at least temporarily, you can go in and find that I am, or I am that, has characteristics and actually has a — the ineffable soul or personal essence actually — actually has, at least in a, you know, kind of helpful way has some parsing that you can you can figure oh, I’ve got strength in me. Oh, I’ve got will in me. Oh, I’ve got value in me. Oh, I’ve got compassion in me. Oh, I’ve got personal love in me. They are — these colors represent concepts like those that are instead of noticing that their mental concepts feel like, wow, those might actually be stored inside me and be primal to me. [00:38:15.07] And maybe I can act out of — maybe I can trust that it’s okay to act out of them. And I don’t have to think that I have to pretend to act out of them by doing it in a socially acceptable way. [00:38:27.02] Maybe if I trust myself and trust — turns out, I think we’re rigged to the good and we don’t have to be but we are. And if I trust myself that I don’t have to have a system of ethics in order to work through the world that I can actually go inside and a better system of ethics that isn’t actually a system of ethics will keep me moving and I can function in it, then all of a sudden, I’m going to be even more appropriate than I was — I, you know, I may not be — I may not join the military, I may be more likely to become a nurse, but I’m still going to be a social being and I’m still going to be an appropriate social being. [00:39:03.17] And I’m probably going to be kinder, because I’m going to probably notice that, wow, everybody has these things in them. They’re all just like me, and they’re just suffering if they’re being mean to me.

[00:39:15.01]

DAVID:

Yeah, it’s a very Buddhist view to speak of innate goodness.

[00:39:20.11]

Neal Allen:

Yeah. And everybody argues about it. And are — you know, do we need to be have innate goodness? Or are we — you know, and I think that’s all well and good to study it and question it and look at babies and see whether they or whatever. But the real thing to do is see if you can experience inside your own self, a capacity for inner goodness and whether it’s inborn or not. I tend to think it’s inborn. Whether it’s inborn or not, it is certainly available to me and I can act with it. And what is the difference between my seeking inner goodness and my deciding functionally, oh maybe I want to be kind in this life. And I lucked out — I met the kindest person in the world. And so I’m allowed to be kind a fairly good portion of the day. And it also helps living on the west coast. I grew up —

[00:40:18.12]

DAVID:

She makes it easy for you to be kind?

[00:40:21.03]

Neal Allen:

She does.

[00:40:22.08]

Anne Lamott:

I said that was all I wanted. I mean, I actually wanted someone that was brilliant. And he — and I wanted somebody with a great sense of humor. And he has that and I wanted somebody who is a spiritually driven — whose spirituality and search for truth was really the operating center of their life. But I said about 10 days in, I said, all I want is sweetness. All I want is somebody who will really, really be sweet to me.

[00:40:51.08]

DAVID:

I love hearing that I — I do the same thing. I command sweetness. I’m like, I want it! Be sweet to me. I want to be like a little kid like — knows of a kitty cat or something like a puppy. You know, like — like for babies.

[00:41:04.21]

Neal Allen:

The funny thing is — and this is in the book that our default love, the love that we come into the world with most strongly — the love of — that a — that you really see kind of emerging and just bursting out of a two year old or a three year old, right? That kind of inquisitive love, it’s there for the two year old. It’s the exact same thing in me today as a 65 year old. And it’s a little embarrassing that at heart, I’m this goofy little kid rolling down a hill, and that that’s who I really — if I really want to get to know who I am, I better get to know that person. And that person doesn’t — it’s weird, because that person looks very, very childlike. And it’s hard to like spend time with it without being scared that it — it’s childish and immature. And it doesn’t belong in the world of — or in the body of a 65 year old. But embarrassingly, that’s who I am. I’m just — I’m a kid rolling down a hill at heart.

[00:42:07.20]

DAVID:

I love hearing that.

[00:42:10.11]

Neal Allen:

We’re a little girl with our Easy Bake Oven. Right?

[00:42:13.11]

DAVID:

And I kind of wonder like, what type of society do we want to live in? The type where we can roll down hills are the type that we can’t, because it’s not allowed, you know. I’m not that young. And I feel like I have a lot of kindness and child nature of things in me. And I just want to enjoy life and be sweet and talk about metaphysics and do all the fun stuff. And I’m really — I really feel what you’re saying. So I think we should be able to grow up old, numerically old and still have a child’s heart.

[00:42:45.19]

Anne Lamott:

The one thing as we start to close up that I really want to draw attention to is that when all is said and done, the gift of doing this work with Neal and reading the book Shapes of Truth and discovering that these feelings inside of me that begin usually clenched and uptight or sad can lead me to the great child blessing of curiosity. And when I’ve got — and that’s what Neal’s secret is that he knows that a lot of people have forgotten that joy is curiosity. Curiosity is joy. [00:43:25.01] And if you can re-familiarize yourself with that feeling of wonder and your mouth hanging open, because you’re pretty much — you’re like 25 years younger than we are. But you know, you lose it by about five, because it’s not the most efficient way for your teachers to size you up and to get you prepared for first grade. It’s that cur — oh that’s sweet, that’s adorable that kids go out and they see a dandelion fluff, you know, and they could stare at it for half an hour. It’s — where it’s really what they should be doing is starting to memorize the times tables, and to be given back even just the word curiosity as a attribute of God. I mean, all of these shapes and colors are attributes of God. And to just be left with the word curiosity, and just sort of keep it tucked in your cheek, like a lozenge or a lifesaver or something can change your whole day around. That like yesterday, we saw three monarch butterflies on our property and we’ve been having a tragic — a monarch tragedy for years now because of climate change. And today, I was walking along and I had to get back here for this and — and I saw one more monarch out — out down the road just — and it stopped me in my tracks and it was like standing next to a Buddhist gong. And it was like God and in her distressing guise as a monarch, just flying and fluttering in the breeze and I was — I was molecularly changed by the curiosity that I felt. [00:44:57.18] So that’s what if — if, you know, there’s talk of, you know, metaphysical kinesiology. But really, it’s about awe. It’s being re — re-awakened to curiosity and wonder and awe. And one of the ways we can do that is to trust somebody else to sit with us while we go deep into what it first seemed traveling, but which turns into the balloon, the pearls, the butterfly, the dandelion fluff, which is really where all the action is.

[00:45:28.13]

DAVID:

Yes, thank you for sharing that. Yeah. So I just got one more question for y’all. And I’ll let y’all go. So I came across a description that spoke about 35 divine objects that represent aspects of God. And I was curious, could you explain what these 35 objects are? Maybe not all of them, but just maybe we can focus on a couple of them? And how they were discovered? And also, are they intentionally arranged chronologically? Or are they of equal value of each other?

[00:45:56.17]

Anne Lamott:

That’s a great question.

[00:45:58.05]

Neal Allen:

That is a great question. So the 35 — we’ve mentioned a number of them. So they’re — the book actually lists them and catalogues them, and I’m looking for one of the lists so I can run through them very quickly. What they represent — they’re kind of — each of them represents an abstract noun at value that you know, as a — as a word or a phrase. They’re words like acceptance, surrender, vulnerability, gratitude, brilliancy value. [00:46:30.03] So you notice when you start hearing those words, they sort of add up as, oh, if I was to describe kind of the highest reaches of what it would be to lead a life of virtue, these would be the kind of things that I would need in order to function in a glorious life of God or without fault or without evil in me. So they’re all on the good side of good and bad and all on the right side of right and wrong.

[00:47:02.11]

Anne Lamott:

Why don’t you tell him just about amber?

[00:47:03.22]

Neal Allen:

Yeah, amber is — is a weird one. Most people don’t — it’s a tough one actually, to find. Usually, people have found a dozen before they find amber because it’s so confusing at first. So Amber, which shows up inside you often as it might just be the color amber. But the color amber is a particular kind of color, because it has that smoky interior. And so often amber shows up as an amber stone, it’s more likely to be an actual solid stone. For instance, the red of strength will most commonly just show up as red, right? It can be attached to anything, or it can just be floating as a redness floating around inside me. But the amber shows up as the rock. And the odd thing about intrinsic value is it doesn’t make sense at first, because I think that value means something that is — that is necessarily transactional. I get my value from the outside. Somebody ascribes value to me, I build up. I lose value by not being productive. I gain value by being productive. It’s like money, right? I’m exchanging my work for getting value in return. If I’ve done — if I’m a movie star, I’m valuable. I have more value as the CEO than as the shipping clerk, right? [00:48:24.02] And so value seems to be tied very tightly to hierarchical views of life, and also to an external exchange of goods. They may be conceptual goods, or physical goods, but there’s an exchange. So let’s say I’m worried about my value. And I go inside. And I’ve done a bunch of this work before. And I’ve done this a bunch of times, and I’m starting to think about, God, I always have this voice in me that says, I’m kind of worthless, or I have to do something to have worth. I want to work on that, right. And so my body accepts that. And I go inside, and I see my emotional difficulty with my own worthlessness. And it appears as a brown or a gray object, and that object then disappears. All the sudden this amber thing shows up inside me. And it feels good, and it looks good. [00:49:15.14] And from that point on, for the rest of my life, I have access to the idea that I was born with intrinsic value. And that value — there is a form of value, that is not an exchange. That is not goods for goods. That isn’t hierarchical, and I was actually born with perfect value. And I can’t add any value, nor can any value be taken away from me. And by the way, I have the exact same amount of value as somebody else. And so now all of a sudden value is almost a different lens on empathy, right? [00:49:53.04] Because that last thing that I noticed that if I have perfect value, so does everybody else. Suddenly it draws me much closer to the — I am sense of myself being the same I am, as Anne is, or as David is, or as anybody is. Then it started my idea of this and noticing this and noticing that this was actually possible. And then noticing it actually feels like it’s real. It started with a little, you know, all I did was, I saw this little piece of amber in this kind of funny little hollowed out section of me. And now I have a capacity for intrinsic value that I didn’t know I had.

[00:50:39.04]

DAVID:

Yeah, oh.

[00:50:40.13]

Anne Lamott:

Yeah, I experience them really as shapes that appear almost inside a snow globe. You know, Neal in the book describes it as almost as if your organs have sort of moved out of the way and there is a hollow space, like a little staging area, and then you get the amber rock. You get the amber stone or you get whatever is going to appear to you that day.

[00:51:03.23]

Neal Allen:

They’re equal in a sense of equal in weight or equal —they’re just kind of perfect things and perfect things are all equal. The way they kind of sort them out — they’ll sort themselves out for Anne differently than for me. So there are five that the Sufi found in the 13th century, the other 30, Hameed Ali found, but the five that the Sufi found, which they call the Lataif, are joy, are curiosity is the other word for it, strength, will, compassion and power. And those five actually, most — people in the diamond approach study them first and for good reason. Because those are five building blocks for a kind of generalized way we function in the world. Curiosity is I want, strength is I can, will is I will, compassion is I am. And power is I know. If I can feel that I have the support of those five things. Then, in my functioning in the world, I can move comfortably or confidently through any kind of moment that arrives, because most moments, start with curiosity move through a strength and end up in either compassion or power. Right? [00:52:25.12] And, oh, there’s will in there too. I have to be steadfast to complete the moment. And curiosity, it turns out, I start to notice, it’s not just a yellow thing. It’s not just a concept. It’s also the thing that appears at the beginning of every single moment of my life. Where every thought, every project, everything starts with kind of I want, I’m curious, I feel effervescent, and just looking around for a new puzzle to figure out. [00:52:52.14] So those five are distinct. Now, I might feel like, I have no problem with curiosity. I’ve always been a curious person. But you might have been told curiosity kills the cat when you were a kid. And so you feel you’re deficient in curiosity. And so you’re going to spend a whole lot of time going into your feeling of deficiency of curiosity, when doing this — this activity, and you’re gonna want to see that yellow show up a number of times before you’re going to be convinced that that yellow is you. Because you’ve got a lifetime of rejecting the possibility that you’re by nature a curious person, you’ve just been lied to by the world that you’re not naturally curious. [00:53:37.05] You are — everybody is. I had to struggle with strength and will. I thought that I was faking being good at doing things and that I — I was a one trick pony. And I wasn’t very strong and I had to work really hard and a lot — lot of — I had to see that red come up a lot of different times before I became convinced that was me. [00:53:59.15] And that I actually wasn’t lacking in strength or discriminatory powers. I was actually just telling myself I was lacking in those things. It turns out we’re all — if you’re alive, you’re perfectly capable of the functions of the world. You know, most — most people are. There’s some people with disorganized minds, but not that many.

[00:54:20.09]

DAVID:

I was gonna say these are things that we’re born with, and that we need to nurture a bit. And by seeing our personal worth, we are able to see other people’s worth. So it almost creates like a softer nature of ourselves. And so in the world we work in as well.

[00:54:34.03]

Neal Allen:

Yeah, I mean we know that intuitively, that we have friends who have this kind of confidence and a kind of truth — you know, we recognize that it’s a kind of true sense of self worth that isn’t putting on the dog, right? That isn’t a filter for the world. And all of those friends are really friendly. They’re really nice people. You know once you’ve decided you’re not worthless and you’re not lousy at life, you’re going to — you’re going to be a kinder person. I don’t know why. I don’t know why it’s rigged that way. It just tends to be.

[00:55:09.23]

DAVID:

It flows easier. Well, it was such an honor speaking with you, two. And before we go, can you just let our listeners know like where they can find your book?

[00:55:19.12]

Anne Lamott:

Yeah, Shapes of Truth is — it’s kind of anywhere you buy books, it’s best karmically to buy a book at the nearest independent bookstore if you want to get a better seat in heaven. And — but if you need it today, which you may, you can get it at Amazon. So you can get it a Boulder Books, you can get it at Tattered Cover, you can get it wherever you shop, for books, or on Amazon.

[00:55:42.09]

Neal Allen:

And if you’re doing e-books, it’s on all the e-book platforms. So you can find it at any of the e-book platforms. And my website, which tells you a little bit about this and has some essays and some other things is Shapes of Truth.com.

[00:56:00.10]

DAVID:

Okay, great. And we all definitely want a seat at Heaven’s Gate, so you know, support your local bookstore. Oh man, it was — it was such a pleasure just speaking with you and just listening to you as well. And I’m really excited to dive into this book myself. And it was just such a pleasure to like, reactivate the podcast with you two. And it’s gonna be such a journey from here on out. And thank you so much for speaking with us today. And yeah —

[00:56:26.11]

Anne Lamott:

Thank you so much, David, and thanks so much Naropa.

[00:56:27.15]

Neal Allen:

This was very fun. Thank you.

[00:56:30.23]

Anne Lamott:

Really loved it. Thanks. Okay. Bye.

[00:56:33.15]

DAVID:

All right, thank you. Bye, everyone.

[MUSIC]

On behalf of the Naropa community, thank you for listening to Mindful U. The official podcast of Naropa University. Check us out at www.naropa.edu or follow us on social media for more updates.