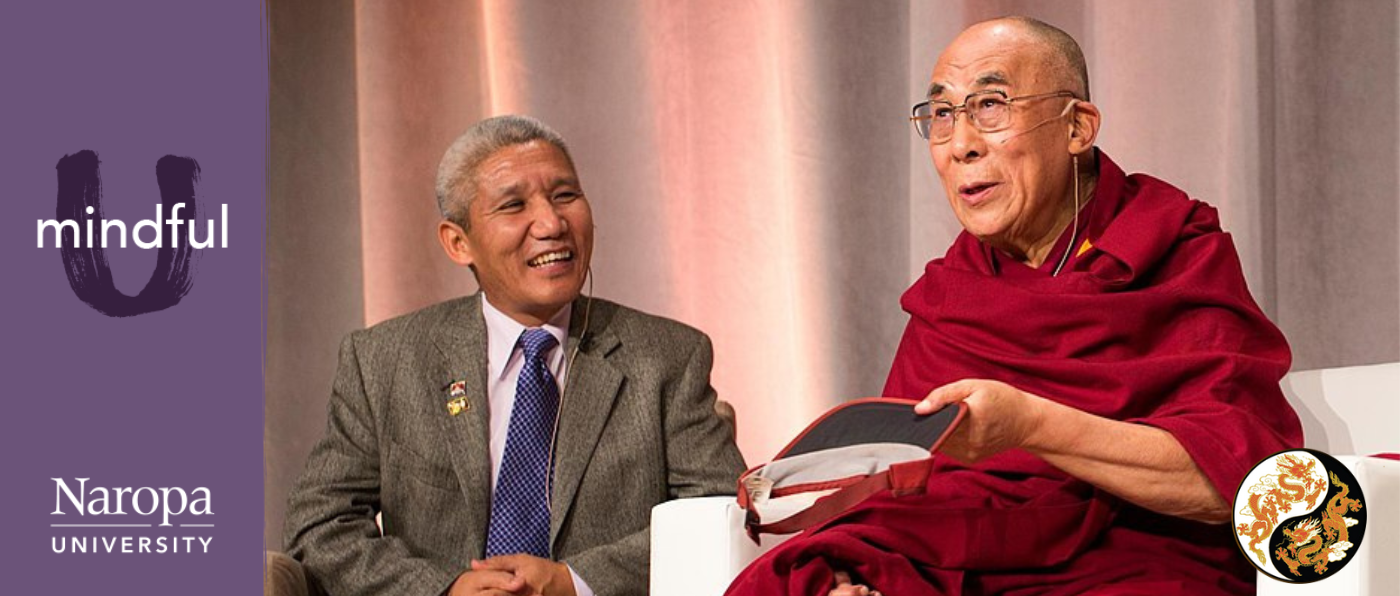

The newest episode of our podcast, Mindful U, is out on Apple, Spotify, and Stitcher now! We are honored to announce this week’s episode features Thupten Jinpa Langri, principal English Translator to the Dalai Lama and Spring 2022 Lenz Distinguished Lecture Speaker at Naropa University.

The 14th Dalai Lama’s wisdom is largely accessible to the English-speaking world because of today’s honorary guest. In this episode, we hear Thupten Jinpa speak fondly of his monk-hood as a compassionate Tibetan child, the divine alignment that cast him as the chief English translator to the Dalai Lama, and his appreciation for contemplative educational values modeled by schools like Naropa. Please join us as we welcome our inspiring friend to the Mindful U Podcast.

Please share this episode with a compassionate friend of yours. Subscribe to the Mindful U Podcast for more educational conversations like this.

Wisdom & Traditions Department of Naropa University

View Thupten Jingpa’s Lenz Distinguished Lecture for Naropa on YouTube

The Institute of Tibetan Classics – Founded By Thupten Jingpa

Visit the Frederick Lenz Foundation

Full Transcript Below

Full Transcript Thupten Jinpa Langri TRT 56:34 [MUSIC] Hello, and welcome to Mindful U at Naropa. A podcast presented by Naropa University in Boulder, Colorado. I’m your host, David Devine. And it’s a pleasure to welcome you. Joining the best of Eastern and Western educational traditions — Naropa is the birthplace of the modern mindfulness movement. [MUSIC] David: Hello, everyone, and welcome to another episode of the Mindful U Podcast. Today we are very blessed to have a special guest. Thupten Jinpa. Jinpa is the interpreter to His Holiness, the Dalai Lama, an accomplished writer, a Tibetan Buddhist scholar, an academic of eastern and western philosophies, a teacher, and the founder of the Compassion Institute. It is our honor to speak with him today. And he is also presenting at Naropa University tomorrow for the Lenz Foundation. And we’re really honored to have him. And I just want to say, how are you doing today? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Thank you, David, for inviting me on your podcast, Mindful U. And as you mentioned, that this is part of a series of events connected with, you know, tomorrow’s lecture that I’m delivering at Naropa University, the Lenz Distinguished Lecture Series. David: Beautiful, yes, we’re so happy to have you. And so, you know, just to jump right into it, while I was researching you, I’ve noticed there was a series of events that allowed you to create a unique educational path for yourself from growing up in a boarding school, developing an interest in spirituality, learning English, becoming the interpreter to His Holiness. You studied at Cambridge University as a student. You became a teacher, then you developed the Compassion Institute. You’ve done so many things. And I’m curious for our listeners, could you briefly describe this journey that you’ve taken, and also the interests while you were learning all these things along the way? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Thank you for your interest, actually, if we look back at my life, it feels as if there was a conscious plan or a trajectory. But to be frank, it was more organic. I was, you know, I grew up as part of the first generation of the Tibetan refugee children in India, the early 60s. And part of that experience was to be separated from our parents and put into boarding school, which was set up specifically for the Tibetans. So that’s how my first years of school began. And then later, while I was at one of the Tibetan refugee schools, a group of monks came to visit us. Later, I found that it was part of the teacher training. And my abiding, kind of enduring memories of my boarding schools were two things. One, is hunger, the food was really poor. David: Oh no. Thupten Jinpa Langri: And the second one was boredom. I wasn’t intellectually challenged. David: It was a boarding school, wasn’t it? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yes, I know. So, when the monks turned up, they spent about a month and each of the classes was assigned one monastic member. And the monk who was assigned to our class taught us basic debating skills, in elementary debate. So, this is part of the Tibetan monastic education system, later I found out. And I was fascinated! So as a kid of about nine years old, I just wanted to be like them, you know, like these monks, you know, I associate the monk with, you know, intellect and great mind and this sharp, quick mind — analytic. David: Such a young age too. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yes. So, I was really struck by this. And of course, also — also, there were two permanent resident monk teachers at our school. And among all the teachers, those two monks also had a sense of serenity, calmness, and even physically in terms of their dress and clothes, they looked kind of clean. So, there was a kind of a — almost like a kind of a glow to their appearance. So, all of this struck me deeply. So, I just wanted to become a monk. So that’s why I chose to become a monk. And then initially, I ended up in a small monastery, which was not a really an academic monastery. So, it took a while before I finally found my feet in a real academic monastic community. And while I was there, then I had more opportunities. My command of English really came more as a coincidence. When I left school, after grade four, to become a month, I had the basic ability to read English, I couldn’t speak, but the monastery at that time was based in Dharamsala in northern India, where — you know our current residence is based. This is in the early 70s, it was at the height of the hippie movement. You know, there were a lot of Westerners coming to India, staying for long periods of time, and learning about Buddhism. Where the monastery was located is in a forest. And this was quite close to many places where some of these Westerners will stay. So, I seize the opportunity to be able to converse with them, and then learn English improving it, and that’s how I managed to learn English. And then once I began to improve my English, of course, then a whole other world was open — became open to me. So that’s what then eventually led to, you know, accidentally becoming a, the Dalai Lama translator, which then — David: Auspiciously. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yeah. Which then made me seriously think about formally improving my English, to get a formal Western education so that I could serve him better. So, which then led me to go into Cambridge. And then the rest is basically history, yeah. David: That’s beautiful. It’s almost like someone’s interest in your culture, made you interested in their culture? It’s like you guys traded? Thupten Jinpa Langri: It is. Yeah. David: That’s so beautiful. So, I mean, in a sense, you weren’t essentially looking to do English, but you just found people there that allowed you to learn it, right? So, you had — Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yes. Yes. David: Mentors that were from the English world. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Exactly. And also, one of the amazing things about English is that once you have a basic command of the language, a whole world, another world opens to you. So, imagine, as a young kid, an early teen, being able to start reading comics, you know, and, you know, so the whole kind of, you know, there’s a history of the world, Victorian history of the world. So, none of these are available in Tibetan. So, once I began to improve my English, then I realized its usefulness. And it brought a level of joy, which is not open to me, you know, through learning about the world, you know, through learning about the world and history and other cultures. And so that’s what then made me much more motivated. It was initially as a kind of a hobby, actually. David: Yeah. So, you became a monk after fourth grade? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yes. Yeah. David: Wow. I mean, I don’t even know what I was doing in fourth grade. It feels like such a thing to take on. How did that happen? Did you get any pushback from friends? Or — Thupten Jinpa Langri: Well, actually, joining a monastery is not that uncommon thing among Tibetans, because historically, or traditionally, monasteries were pretty much the only place where someone could get an education in Tibet, in an old Tibet. So, the, you know, membership of the monastery is quite large. But what was unusual was that in India, in the exile community, that time it was fairly rare, because imagine my parents’ generation, the newly arrived refugees, don’t speak the language of India, are forced to do manual laborers like road construction camps. And then they see their children going to school, and they see school education associated with employment. So, someone who has an opportunity to have received education — formal education, becoming a monk was at that time, not that common. So, my father, my — unfortunately, sadly, my mother had already passed by then. But my father was, at that time, he himself had become a monk, but he was quite opposed to the idea of me joining a monastery because I was doing well at school. And, you know, I have two younger siblings. So, he probably saw me as someone who’s going to take responsibility when I grew up. Get a job, you know? So, there was a push back from him. But I was so inspired by the examples of the monks in the schools that I just wanted to be like them. So, I think something was pulling me. David: Yeah, I mean, the radiant-ness is very attractable. So, it’s something that I think all people want to emulate. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Exactly. And find it us, you know? David: Yeah, very cool. So, I’ve noticed you have a very interesting educational path because you studied Tibetan Buddhism, you’ve also studied Eastern philosophy and Western philosophy. So, you study these — you’ve studied like many spiritualities and philosophies, and they’re all coming together. I’m curious why the study of these philosophies? And have you noticed a common theme between these different ideologies, and the way they express themselves? Thupten Jinpa Langri: That’s an interesting question. I mean to be honest, when I began to formally study at Cambridge, the choice of philosophy was a pragmatic one, because I knew that doing an undergraduate you know, in North America, it’s four years but in the UK, it’s three years. And three years is a substantial period of time. And so, I had to be smart in choosing what subjects I wanted to study. Because my primary aim was not so much the content itself, but more the ability to have an opportunity to formally perfect my English, to have a professional English. So, choice of philosophy was more of a secondary, partly because I felt philosophy is probably the modern discipline that has the closest affinity to the monastic academic training I went through. And also, my understanding was that learning — doing philosophy degree, might also help me in my interpretation of Buddhist philosophical ideas in English. And hence be more capable in serving his holiness in an efficient way. So — so it’s not so much that I had a personal quest that I was, you know, following, by choosing philosophy, it was more of a pragmatic decision to choose philosophy, yeah. David: It seems as though if you’re learning English, philosophy might be hard, because it’s ideologies, it’s spirit based. So, some of the things we talk about aren’t so concrete, it’s not like I hold a cup. This is a cup. It’s like this is the way I feel. So — Thupten Jinpa Langri: It’s true, true. David: So it probably accelerated your understanding of English. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yes, and also, one of the challenges when you’re translating across languages, is not so much when you’re translating everyday facts of experience, you know, that are easily translatable in ordinary, you know, through plain English, but where our challenges really come is at the level of abstract ideas. And so there looking back my choice of taking philosophy, as my focus of study at the undergraduate level was a good one, because I came to realize is that, you know, as human beings, I do believe that there are, at a very fundamental level, certain commonalities, which, if you want to constrain us to think about the world, in a particular — in certain patterns, in certain broadly, similar patterns. But at the same time, I think if you look at Buddhist philosophy, versus Western philosophy, I mean Western philosophy is a vast world, but I mean broadly, if we sort of contrast the two. The way in which we divide the world is slightly different. Okay. And this division is something that is necessary because for human beings to make sense of it — of their experience of the world, you have to create categories, and impose that categories on your experience of the world, perception of the world and then make sense. And this, you can call it the conceptual map, if you want. So, the conceptual mapping is never going to be exactly one to one correlation. But at a broader level, they tend to do the same kind of thing. Okay, so that was what was very interesting about studying Western philosophy, after having been deeply immersed in Buddhist philosophy, and studying formal discipline, like philosophy, help someone like me, whose native language is not English, to be able to think in abstract terms in English, which is really crucial for someone who’s translating, because translation, you know, is not naive reproduction, replication of one word into another different languages word. Often, translation is more at the structural conceptual level. So, to have a deeper appreciation of the language of English, in particularly in philosophy was really helpful. David: Yeah, yeah. Okay, that sounds great. So, you’re going to be speaking at Naropa University for the Lenz Foundation. You’re one of the guest speakers. And Naropa University is a contemplative education. So, we have a different approach. I’m actually a graduate. I graduated in 2012. I have a contemplative Buddhist degree and BA. And I also studied music because I really love music as well. So, I really found it profound having a contemplative approach to education. And I’m curious, could you speak upon how important it is nowadays in the world that we live in, of a contemplative education approach to our, you know, endeavors when we’re learning? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yeah, thank you for bringing that — bringing up that question. Because, you know, if you look at — and this is one area where His Holiness the Dalai Lama has been very vocal, the need to introduce some fundamental level reforms, though very, not only the system, but the very philosophy behind education. And I think he’s right. Because one of the things is that up until very recently, the focus in modern education has been very, very kind of a material paradigm, and almost to the point where, even though they are humanities subjects, but, you know, broadly, education is really seen as a way of preparing someone to be employed. So, there’s a very utilitarian attitude. And furthermore, in education, there’s very little focus paid on what it means to be a human, how to live. That initially, if you look at the Greek tradition, which is the original kind of roots of Western educational system, we do find instructions on ethics, philosophy, and so on and so forth. But over time, in modern version, at least, there’s very little explicit focus. And ethics sometimes is assumed to be a part of religion. And since the education space is secular, then you don’t need to teach ethics kind of, you know, there’s that naive assumption. So, all of these, you know, sort of makes it very difficult to bring up, you know, many aspects of education that are really crucial for human beings, you know, what is the ethical development of a child? What is the individual’s responsibility towards others, you know, fellow humans and the world? How can we, you know, have a deeper self awareness in relation to our own emotional life? And how can we sort of, you know, tap into the more positive aspects of human nature, so that we can create a world that is kinder, more equitable, you know, a place of understanding. So, all of these, you know, we may call contemplative, but contemplative I hear, from my own personal understanding, I understand the word contemplative, as a way of bringing an approach that emphasizes self awareness, paying attention, and also bringing conscious intention into what you do. And tempered with, you know, important fundamental human values that we share. And if we broadly mean this by the word contemplative, then clearly, this is something that needs to be, you know, brought into any education system across the world. Because, even though you may speak different languages, may live in different parts of the world. But when it comes to fundamental human reality, we are all sharing this one small planet, which is now facing existential threat from climate crisis, as well as, you know, the pressures of globalization, putting on all of us to really find a way to live where peaceful coexistence based on mutual respect and understanding becomes an important part of our challenge, important part of the requirement, if we want to save the world, you know. So, in all of these, some element of contemplative education has to be necessary. And things — you know, the skills that we can teach children about how to pay greater attention to one’s own emotion, how to bring awareness into a situation, how to maintain a more mental composure, in the face of a challenge, how to be more resilient, and how to treat others, based on recognition of shared common human humanity. So, all of these are really crucial issues. So, I think you’re lucky to have been able to go to a college that actually explicitly states these to be part of the educational approach. But I hope that you know, more and more institutions, educational institutions will come to recognize it. I mean, and one hopeful sign is that at least, there is a cultural movement towards bringing social emotional learning into the education system. So social emotional learning does not do the whole thing, but I think it’s a really good start, because it starts with emphasis on awareness of one’s own emotional life, and social awareness of the needs of others, and human relationships. So, I think a large part of what contemplative education aims to cultivate seems to be, you know, achieved through focusing on social emotional learning. So, I’m quite optimistic that this movement is turning out to be quite successful. David: Beautiful. Yeah. And honestly, when I went to Naropa — I went to Naropa as a 27 year old so I wasn’t just out of high school. It was very foreign to me to have eye gazing practices, and something I’m not used to, but now that I’m an adult, and I’m stepping into my power, and I’m more conscious in what’s around me, I realize the importance of social emotional learning, and also at what I’m hearing is the relationship to the content is beyond the content. And so, relationship to self, it’s the relationships to others. And it’s a relationship to the content. It’s not just content. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yeah, exactly. David: It’s — as you were saying, like repeating something. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yeah. And the interesting thing about, or it could be also seen as the challenging thing about these kinds of education is that it’s not so much content mastery, because the traditional education in many academic institutions is really content mastery. You — you take note of the lectures, you learn the regurgitated, you reproduce them, you have lists, but contemplative education, including social emotional learning, involves something beyond content learning, it involves doing it, and you learn by doing it. And a large part of that is also learning to embody it. Because you have to — without embodying these values, these, you know, aspects of education, then the transmission of them do not become that effective. So that’s — that’s the interesting part about this. David: Beautiful. Okay. So, we’re gonna kind of like change the subject a little bit, because I want to talk a little bit about translating. And so, you’ve been translating for His Holiness, the Dalai Lama for quite some time now. And I’m curious, how did you become the translator? Because it seemed like you became the translator while you’re at Cambridge? And also, what kind of content do you translate for him? Is it like books? Is it conversations? Is it live events? Is it just personal event spaces? Or you just — you do all of the above? In what capacity do you show up, I guess? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Well, actually, I began translating for him before my Cambridge years, it was in 1985. And it was more of a — it happened more out of a coincidence. I happen to be in Dharamsala. I was in my mid 20s. And His Holiness was scheduled to give a series of teachings and the translator that they have arranged was unable to make it on the first day of the teaching, which was already scheduled, and they were looking for someone to stand for that person. I happened to be in Dharamsala, and the word got around that there is this young monk who has a reasonable — reasonable command of English. So — David: And that’s you. Thupten Jinpa Langri: So that was me. And then I was plucked out of my seat where I was sitting outside in the veranda of the temple. So, I was asked to translate. This then led to, of course, eventually becoming principal interpreter. In fact, my studies in Cambridge was primarily motivated by sort of, you know, equipping myself with a greater efficiency to be able to serve the Dalai Lama, in my translators’ role. That was one of the principal motivations for going to Cambridge. But initially, I was traveling extensively with His Holiness. My travels began first in — within India, and then from ’87, for his international trips. So, when he visited North America, UK, or other parts of Europe, especially when the onstage language was an English, I would accompany him. And then every year in Dharamsala, there is a major spring teaching that he would give immediately after the Tibetan New Year and prayer festivals are over. So, then he would give sometimes running up to two weeks or three weeks teachings, which will be translated simultaneously. So, I did that couple of years, although I was based in South India, as I was still a student at Gunden. So, I will travel up to Dharamsala for the spring teachings. And then gradually, I also began to assist him on his major book projects. For example, like his “Ethics for the New Millennium,” which was a major book, setting out his philosophy of, you know, secular ethics, in a kind of a more universal way, not grounded in any particular religious beliefs or views. And then he’s other books such as “Universe in a Single Atom,” which tells his story of engagement with science over many, many decades. And then “Beyond Religion” was another book that was a sequel to “Ethics for the New Millennium.” And then another book that I assisted him was, you know, towards the true kinship of faiths, which is — which tells his story of many years of engagement with religious leaders and religious communities. So, it’s, it’s a religious journey. So, I had the privilege to serve Him and for these major book projects, I, you know, had to go to Dharamsala quite often to sit down with him days at a time, you know, sometimes two hour sessions in the afternoon and so it was a real privilege. So, I assist him when he’s traveling. And also, another important series of conferences that I’ve had the privilege to serve Him are the Mind and Life Dialogues, which began in 1987. And every two years there was a major Mind and Life Dialogue which takes place over a period of five days from Monday to Friday. So those, you know, I had the privilege to translate for him. So, these are services that are offering him. David: Well Mind and Life, is that with Dan Siegel. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Dan Siegel presented at one of the — but the Mind and Life Institute is based right now in Charlottesville, Virginia. It used to be actually based in Boulder, Colorado. David: Oh! Yeah, hometown. That’s where I’m at right now. Thupten Jinpa Langri: It moved to Charlottesville. Before that it moved to Massachusetts. But it’s been there for a long, long time. And it’s the — it’s an organization that was co-founded by his holiness with Francisco Varela, who’s a quite a well known Chilean scientist in Paris, and then a businessman, man, local to Boulder, by the name of Adam Engle, the two of them co-founded Mind and Life Institute, and had been running these series of dialogues with a group of scientists with His Holiness every year — every time it’s a different group of scientists, depending upon the topic. And the extensive dialogues take place in — at his residence, Dalai Lama’s residence in Dharamsala. And the many of these have come out — the proceedings have come out in books. David: That’s beautiful. I had no idea it was located in Boulder. So, I just learned something new. Okay, so you’ve been the English interpreter for His Holiness for quite some time now. And you’ve obviously traveled the world, you’ve been by his side for a long time, and you know him really well. And I’m curious, how has his understanding of English developed over that time? Because I’m sure at some point, he’s like, got it going on, knows the language and just needs you for some reference? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yes, in fact, people will notice that quite often, when he gives a public talk, he speaks entirely in English. So, I’m there just as a, you know, a standby, just in case needed. So, he’s come out of English, he is very good. I mean, of course, because he doesn’t hang out, like ordinary people in coffee shops and stuff. I mean, his fluency is not there. Whereas, you know, I had the opportunity to be in Cambridge and hang out and just be an ordinary — lead an ordinary life, using English on a daily basis as part of my everyday life. But otherwise, I mean, if you look at His holiness, his range of vocabulary, it’s really extensive. And in fact, when people present to him even in scientific conferences, quite often, we aim to have the presentations prepared by the scientists in such a way that His Holiness can follow the presentation entirely in English. Then when he responds and ask questions, then when he’s digging deeper into Buddhist philosophy, then he might use me to assist him in the translation. But his command is actually really good. And — and, of course, he’s been exposed to English language for a long, long time. And his vocabulary ranges very, very fast. So, and there, I remember sometimes, you know, we would be speaking at the formal events, and I would be standing next to him, and I didn’t have to say a single word. So then, you know, people who are listening to the dialogue for the first time, wondering what is this short guy doing next to him? Small guy doing next to him? David: Yeah. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Once I was at a luncheon, and then when His Holiness stood up, then I had to stand beside him. And then when the — it was over, I didn’t have to do anything. So, I came — and someone that is sitting at my table said, so why are you standing next to him? You know, so I said, well, you can guess that I’m just too small for a bodyguard. LAUGHS. I said I am his interpreter just in case — David: I mean, you never know. You might have some you know, Kung Fu in you or something. Thupten Jinpa Langri: I said, you can guess I’m not a bodyguard. LAUGHS David: Oh, that’s awesome. So okay, what you just said kind of leads into my next question. And I’m wondering, when you’re interpreting English and Tibetan, there seems like a very big gap of talking about a computer or you know, things that are easy to talk about them. But then there’s the ideologies, there’s philosophies. And I’m curious, does Tibetan translate to English well, when it comes to spirituality and or philosophies? Because it seems like the Dalai Lama has, you know, he can speak English but then you come in when you’re talking about deeper spiritual concepts. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Sure. Sure. Ralph Waldo Emerson said something, which I actually deeply agree, and he said that any important insight into human nature, any profound experience that human beings have, can be — you know, that is articulable in one language should be translatable into another language, and I completely agree with him. So, but this said, it is almost impossible to be able to have a translation strategy where you completely mirror the two languages based on a one to one correspondence of words across the two languages. The translation doesn’t work like this, although some people strive to have that kind of fidelity to the literals you know, a translation but on the hole, most translators understand that that is — that is a myth, that as a kind of an ideal that is impossible. So, the translation really takes place more at the level of phrases and sentences. And so, what is conveyed in one sentence, I believe can be conveyed in another sentence. We may not use the exact number of words, and sometimes a single word needs to be translated into a phrase, but I genuinely believe that you can convey the important message from one language into another. And the same goes for Tibetan and English. But there are very few areas where there are certain concepts which are very difficult to convey in another language, in an immediate way. But those are fortunately very rare. And then of course, notoriously, translation of poetry is very difficult, because poetry, a large part of poetic effect, really comes through the aesthetic experience of the tone and energy of the language it is written in. And trying to capture that and to reproduce in a second language, that is a tough one. And similarly, there are literal aspects of a — of a language that is unique to a particular language. And that I don’t think can be replicable. So, beyond these, you know, I think anything that is worth being communicated in one language should be translatable in another language. So — so far, I haven’t really come across a situation where I say, this is impossible. David: I give up. Okay, so I’m just thinking about this right now, is the actual words and the mirroring, like you said, might not translate well, but figuring out a phrase to distinguish what this one word is, but we as humans, we all have a soul, we all have feelings, we all have like the same mechanics, you could say. So, we all have the ability to understand and because we are human, we can fairly understand love, anger, respect, honesty. So, if you’re able to phrase it in such a way that the conceptual meaning can come out, then it is translatable in any language. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yeah. David: Okay. Great. Thupten Jinpa Langri: And I truly believe, I mean, of course, some scholars might, I mean, there are some scholars who actually dispute — question any kind of universality. You know, that was one of the things about this whole enterprise, which people speak less of today, but postmodernism. One of the major challenges that postmodernism raised was the very idea of universal — universalism, but I personally believe that, given the biology of who we are, as humans, and given the very similar evolutionary forces, that has shaped us, as social creatures, there has got to be, at a fundamental level, certain important aspects that are universal. And now then go on to jump to say that there are cultural values, values that are true universally across all cultures, those are kind of slightly more difficult claims to make, but at a fundamental level of human experience, I do believe there are features of who we are as human beings that are universal. And therefore, I agree with Paul Ekman, who really argued for universality of certain basic emotions. You know, he was criticized, but I do agree with him, that you know, when it comes to fundamental aspects of emotional life, there may be even some very, very basic emotions that we share even with not just among humans, but even with non-human primates. Given the similar biological, you know, given that we inherit, and therefore, any important insight in the human condition has to touch upon those universal features of human life. And then, if it has been articulated in one language, it should be translatable. Because in the end, success or failure of translation is not about coming up with words. Success, or failure of a translation has to be judged by the capacity of the understanding in the host language. If something is conveyed from Tibetan text into English, and if the reader in English experiences the effect it is supposed to produce, then that translation is successful. David: Okay, I’m having a thought right now. There are languages that aren’t vocal, they’re more physical. So, like, if I was to hug someone, no matter what language you speak, you understand that someone is caring? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Exactly. Yeah, exactly. David: Even animals. You can see elephants are so loving of their — their young. And we as humans, we’re witnessing love, we’re seeing language happen. Thupten Jinpa Langri: It’s true, exactly. So, I mean, that’s why I think the — you know, we sometimes tend to look at language as something very unique to human beings. And we are so obsessed with defining language purely in terms of words, symbols that we create, but in fact, language has to be better understood in terms of gradations of signification. You know, hugging is a kind of a language because you’re expressing something. Language, ultimately the role of language is to express something. David: Yes. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Okay. So, and the expression is done through some kind of signification and what is signified is the experience or the emotion, okay. So, then non verbal languages or non verbal expressions, those are part of signification symbols that human beings use. So, if we understand language, within that broader context, then we will understand that one is communicable in one formal language, kind of a language, in a linguistic sense, should be translatable, conveyable, in another language, yeah. David: Beautiful. Okay, so this kind of leads me to my next topic, we’re gonna have a little bit more compassion. So, I just want to say one thing I’ve noticed about looking into you, researching you and like looking into your work and listening to your talks, is you’re such a compassionate person. And lately, I’ve been watching a lot of politics, and I was just like, my heart’s kind of like, oh, man, what’s going on with the world. And what I’ve realized is, if you feel lost in the world, and there’s like loyalty and joy and respect or being lost, go talk to a Tibetan Buddhist. Thupten Jinpa Langri — (LAUGHING) David: There’s so much hope and joy and love and compassion, and even respecting parties that aren’t treating people, well, how much compassion they have, and it’s my remedy almost nowadays is to — is to like, think about a Tibetan Buddhist, because in your foundational approach is, we are all good, we’re innately good. And I resonate with that so well, other than being a sinner, it’s like, I’m not a sinner, like, I want to do good, I want to do good for everybody. I have compassion, but we need to cultivate compassion. We need to develop it, you know, and then sometimes it’s hard to see. We need to clean off the lens in which we look through and be able to do that. So, my question to you is, you are currently the chair of the Compassion Institute. And I’m curious, what inspired you to start this institute? And what are your like daily roles in this position? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Well, thank you for the question. It’s not that I’m a more compassionate person than compared to others. But one thing that I have dedicated to do, or chosen to do, is to really amplify the discourse on compassion, so that people can bring greater awareness to its importance because Buddhist teachers include — including especially as long as the Dalai Lama has been reminding us, that in addition to all the dark forces that we human beings naturally have — anger, jealousy, hatred, but we also have good qualities like compassion, empathy, forgiveness, ability to forgive, understand. So, His Holiness has been very, very dedicated to proposing this idea that while we think of human nature, we should never forget, lighter, positive, brighter side of the human condition, which is this ability to connect with someone naturally, to be able to empathize even with this dangerous situation. And to cooperate. You know, so use this cooperation as an expression — behavioral expression, coming out of this ability and instinct to connect. And His Holiness genuinely believes that human society and humanity as a whole will really be changed, if we consciously seek to make that part of who we are more explicit, more forceful, even in thinking about our structure of our society, in thinking about policies that we will bring, thinking about how we treat international relations, and all of this. So, I think His Holiness is right. And my, you know, sort of whole aspiration behind setting up Compassion Institute and developing the eight week CCT, Compassion Cultivation Training, when I was a visiting scholar at Stanford, all of these is really, from my side, at least, an attempt to make part of the Dalai Lama’s vision of spreading compassion more broadly, kind of, you know, real. So, and what we try to do at Compassion Institute is that, I mean, first of all, the Compassion Institute is the institutional home for CCT, which is a eight week compassion training program. And I genuinely believe that it is important for something like this program, there should be an institutional home, that keeps an eye on the integrity and quality of the program that has been developed, which has been tested, verified, you know, findings have been reported. So — so Compassion Institute trains the instructors who are then certified to offer this course — it’s an eight week class. And then more specifically, one of my aspirations, which we are now able to do is to find ways to adapt these secular compassion training to specific important sectors of society like health care, or law enforcement, and education. So, Compassion Institute has taken on three focus areas where we adapt compassion training and bring these programs. So, we have a program called Courageous Heart. And it’s a program specifically designed for law enforcement officers. You know, it’s adapted from the eight week extensive course, but it is a specialized program. And the aim is to train officers to be able to bring more awareness into their emotions. And also learn to pay, be more mindful and — and then connect with their intention. Because, you know, almost all people who are in public service, one of their primary motives have been to be — to serve society. But in the — in the challenges of everyday work, people often lose connection with that original intention that brought them there. The compassion training helps to keep that spark alive. And then also learning ways in which you can see the other person first and foremost, at the fundamental human level, just like me. So, there are clearly important implications for bringing a program like this. Unfortunately, our program has now been certified by California, Peace Officers Training Standard (POST) such is available across the state, hopefully with other states as well. And then we have a special program developed for helping healthcare professionals deal with the problem of burnout. And it’s called Caring from the Inside Out. So, it’s again, adapted from our CCT. And then on the education side, we are collaborating with Renee Crown Institute, which is at Colorado University, and collaborating with the School of Education there to develop a course on compassion and dignity for the in-service teachers, which can contribute towards their master’s program. So, our hope through the institute is to find ways to bring explicit compassion based approaches in the key sectors. So that way, it’s kind of a more strategic approach, so that we don’t rely entirely on individuals self — self selection, and so of course, we have to broaden it by offering the public courses across widely through our network of instructors. But at the same time, if we are serious about changing society, we need to start looking at key sectors, and especially at the public service sectors, because their interaction with the public is a key part of their everyday life. And compassion, the most important aspect of compassion, its relationality. It isn’t about how you treat the fellow human being in front of you. How can you bring your best into that interaction? So, anything that involves public service, being able to bring something like compassion training can have a huge benefit, both to the officials themselves, but also to the recipients of that interaction from the general public side. I mean, imagine if a physician goes through compassion training and is able to bring all the skills of empathy, attentive listening, understanding and sense of concern and clarity into the interaction with patients, that patients experience will be completely different. David: Yes. Thupten Jinpa Langri: So, I mean, you know, we know — it’s a no brainer. David: Yeah, seriously. Thupten Jinpa Langri: But we do need organizations that are dedicated to systematically thinking of, doing the hard legwork of building up relationships, making the case, raising money, you know, training the trainers. So, this is why the Compassion Institute was set up. And I, you know, I’m the Chair. I don’t do the day to day running, it’s based in California. We have a very efficient executive director who runs, by the name of — who runs the organization by the name of Stephen Butler. And I’m very confident that, especially after he took over, I’m feeling very confident that we’re going to be quite successful. David: Beautiful. Doing the good work. So, as you were speaking, what I’m noticing is, compassion isn’t something that we don’t have, and we have to learn how to have, it’s something we already have, we always have it. So, what we have to do is come back to our foundational roots of something that is innately already in us. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Exactly. And that’s the beautiful thing about compassion. It’s not a new skill we have to learn. But what we have to learn is how to make it more intentional, and then how to apply it. And then also deal with some of the other forces that tend to undermine it, come in the way, like, you know, sort of division, discrimination. All of these forces in human nature that come in the way of us being able to express our compassionate nature. David: Yes. Okay. So, we’re talking about compassion and compassion is usually seen as something that is outside of us and being used to alleviate suffering to others, right, because we’re talking about public working services, police officers, fire department, health care workers, but sometimes we forget to be compassionate to ourselves, and we bypass our needs. So, I’m — what I’m curious about is what are some ways to notice this before it becomes an issue in our lives? And how can we consciously develop a skill to be compassionate to others, while also being compassionate to ourselves? Because sometimes, if we try and be compassionate to others, it actually might drain us a bit. Thupten Jinpa Langri: True. David: So how can we withhold it within ourselves? Thupten Jinpa Langri: I think here, a part of the challenge in the West is the West’s tendency to kind of dichotomize things. So, for example, in the West, we tend to overemphasize the self and others distinction. And also, when we think of helping others, we tend to think exclusively in terms of others, rather than our interrelationship with the other who were helping. So, part of the problem is really coming from there. But you’re making — raising an important point, which is about really the legitimate need for self care. And sometimes in the West, people seems to feel that if I, you know, if I think about my own needs, and my own welfare, I’m being selfish. And if I want to be compassionate, I shouldn’t be thinking about my own needs and my own welfare. So that’s, again, that sort of conflict is coming from this very strong dichotomy of self and others. In fact, my suggestion would be to look at the question of one’s own self care needs to put in the broader context of compassion, because compassion, of course, is focused on others. But also, compassion includes your ability to relate to your own suffering and situation as well. And in fact, if you are truly compassionate, and truly altruistic, then the need to take care of your own self becomes necessary for you to be able to make yourself resilient and be available for others. Whereas if you ignore your own need, and part of that is, the solution to that is largely bringing self awareness. If you develop greater self awareness, you begin to recognize what burns you, what tires you, when it’s time to refresh yourself. So self compassion issue, to a large extent, is really about bringing self awareness into our own situation. And we should not couch the issue of self compassion and self care, independent of our compassion for others. In fact, my suggestion would be to actually see it as part of that broader, in a commitment to be compassionate. And then to be compassionate efficiently, then, we also need to have a healthy dose of self compassion and ability to you know, take care of our own needs. And once we see it in this way, there will be no conflict because otherwise we end up creating a sort of a false dichotomy. You know, should I be self compassionate or should I be — ignore myself and be compassionate towards others? So that kind of false dichotomy is in the long run, not really helpful. David: Beautiful. Okay, so I just got one more question for you. And what I’m curious about is when, like, maybe this is a Western thing, and I don’t know, maybe there’s other regions that feel this, but compassion can seem weak. Compassion seems not something that could deal with big situations like we need to — we need to attack things a little bit differently. And so, when teaching compassion as like a foundational base in which we act upon instead of acting from other qualities that aren’t serving our ultimate well being, I’m wondering how this approach can benefit us as individuals in a community and the society. So, like, you know, trying to teach a law enforcement person compassion, instead of like, put them in cuffs, put them in the back of the car, like rough them up a bit, they messed me up, like, how is that powerful? How is this important? How is it not weak? Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yeah, well, that’s a good question, actually, you know, I mean this is one area where His Holiness is very, very articulate. His Holiness says that compassion is not a weakness, because he — he says, compassion is a strength. Because compassion, choosing compassion, makes you open yourself to be vulnerable in the situation, and also giving the other person the benefit of the doubt. Whereas choosing anger instead is an easier option. You know, you just let your anger out. And so, it’s an easier, simpler approach. So, he says that choosing compassion requires courage. And he’s right. But the power of compassion really lies in — in the biggest, for example, even in the case of law enforcement. What is the end objective? The end objective is to be able to sort of really control the situation. Okay. And so then in the case of an interaction with someone, if you use force, you’re using fear as a primary tool of sort of, you know, persuading the other person. But if you instead use a compassion based approach, which will be then indicating that you are willing to listen to their side of the story, you are sort of indicating to the other person that you are also aware of their need for safety. Okay, because often in tense situation, people do things impulsively, without understanding and impulsive action out of fear creates a huge mess. So, the one of the skills that the law enforcement officer can learn through this kind of training is to defuse the immediate tension, so that people can bring their composure into a situation, okay. Similarly, in major situations, you know, when choosing compassion does not ask us not to respond strongly against an unjust action. What it is saying is that, when we choose that strong action, don’t choose it out of anger, don’t choose it out of fear. David: I see, yeah. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Choose it out of an understanding, while remembering the humanity of that person. You know, quite often people do horrible things, because they’re in pain, because they are afraid, okay, because they are confused. So, of course, self protection is important, you have to make sure that danger for your own life you know is prevented. But once you are able to create that, then the impact is very different. I mean, there are stories from the Iraq War, where when American soldiers were — caught themselves in a very tense situation, you know, the leader of the soldiers, being able to understand the cultural context, put the weapon head of the gun down, bowing down, and, you know, just creating sort of releasing that tension initially, has completely changed stories there. So, I think this is where bringing compassion because it asked us to bring clear understanding and awareness into a situation. It’s a tougher one. But the long term effect will be very different actually. David: I’m almost kind of noticing that anger is reactive. And when it comes to compassion, if we don’t practice or study, or apply it, then it’s more of the wait, let’s see how I feel, how it affects me and then react. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Exactly. David: We need to investigate how it’s responding to us and also understanding how you’re saying is loving the other person like nobody really means to do bad things. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Sure. David: We might do bad things, we don’t wake up, like, I’m going to be bad today. Nobody wants to do that. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Yeah. David: We want to be good. And we want to be good to people. So, practicing compassion has the ability to like, take a breath. And I think this is why there’s like meditation practices of like slowing down because we’re such reactive beings. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Exactly. David: The world, like hardens you to be reactive. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Exactly. Yeah. Yeah. And beautifully put. Yeah. David: All right. So that’s our podcast. And I feel so inspired. I like, I just feel like my compassion meter is off the charts right now. Thupten Jinpa Langri — LAUGHING David: And it was just so beautiful talking with you. And you’re just making me feel all the love and all the good stuff. And I just love how you can like talk about your journey, your educational paths, and I look forward to your talk tomorrow at Naropa. And I just really appreciate you speaking on our podcast today. So, thank you so much. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Thank you. Thank you for including me in your series of podcasts. Thank you. David: Beautiful. All right, take care. Thupten Jinpa Langri: Take care too, bye bye. [MUSIC] On behalf of the Naropa community, thank you for listening to Mindful U. The official podcast of Naropa University. Check us out at www.naropa.edu or follow us on social media for more updates.