By Anne Z. Parker PhD, Professor to Environmental Studies at Naropa University and In-Country Director of the Naropa University Bhutan Study Abroad Program

“I am happy to open this conversation and ready to receive critique, since I am a classic example of a white woman from the USA who has the privilege of higher education and has carried out academic research. In fact, I am not only ready for this conversation, I have been waiting for it for 40 years,” I commented at the opening of a public talk as a collaborative team of Bhutanese colleagues, and I launched this topic.

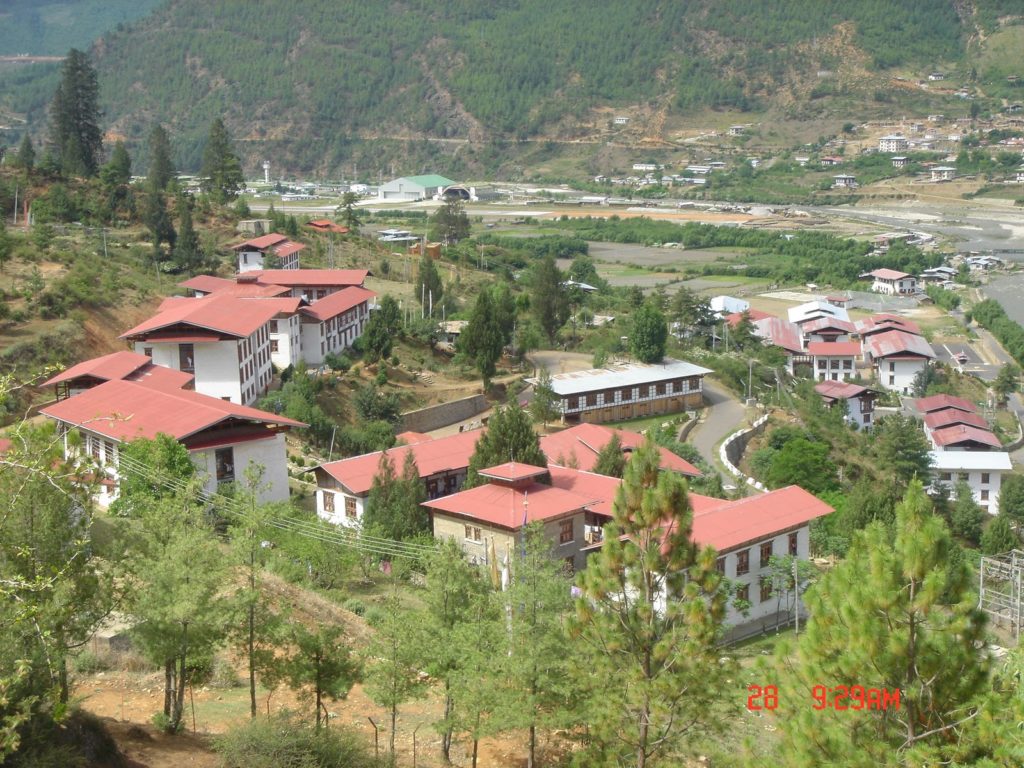

Students, educators, and government officials from the western Bhutan region sat engaged and eager to plunge into the lively conversation. Thus began the second lecture in the Rimpung Lecture Series at Paro College of Education, Royal University of Bhutan. It seemed to be a conversation waiting to happen.

Since the beginning of the Naropa University Bhutan Study Abroad program in 2015, we have worked to actively reframe our approach to research, foregrounding ethics and right relationship, and taking time to live in the culture as ordinary students, seeing as much as possible through on-the-ground intercultural lenses.

We opened the lecture and panel with the unforgettable words of Linda Tuhiwai Smith, “’Research’ is probably one of the dirtiest words in the indigenous world’s vocabulary” [Professor of Indigenous Education at the University of Waikato in Hamilton, New Zealand]. Linda Tuhiwai Smith’s striking statement in her book Decolonizing Methodologies was coming out of the experience of many peoples’ perception of research as something done by outsiders to no apparent positive outcome and that exploited peoples, their cultures, their knowledge, and their resources.

A Bhutanese colleague had warned me gently, but clearly, that the topic could be seen as too conflictual here and coming from an ungrateful stance in this cultural context. So we talked more and when I noted that this was not an angry critique, but a critically important one, she then nodded in agreement, understanding that “The intellectual project of decolonizing research…needs a radical compassion that reaches out, that seeks collaboration and that is open to possibilities that can only be imagined…..It is not a method for revolution in the political sense, but provokes some revolutionary thinking about the roles that knowledge, knowledge production, knowledge hierarchies, and knowledge institutions play in decolonization and social transformation.”

Bhutan has not been directly colonized, so the issues of the directly colonized countries do not initially, or at first glance, resonate here—issues such as experienced in countries that suffered direct oppression, genocide, resource extraction, and forced assimilation in which local, indigenous ways of knowing and ethics were suppressed and left out. Also as places where restoration of sovereignty, self-determination, land rights, and intellectual and cultural property rights are being actively called for. However, Bhutan is a multilingual, multiethnic country so these issues cannot be ignored. The issue of the indirectly colonized countries, where colonizing world views and cultural values remained embedded in media, education, trade goods, and so on in the sense of “the west as better,” have been subtlety infiltrated by core western values: of progress, individualism, and objective positivist stance. There are complex ways in which the pursuit of knowledge is deeply embedded in imperial and colonial practice.

“…Indigenous knowledge as a space of epistemic disobedience that is ‘delinked’ from Western, liberal, capitalistic understandings of “knowledge as production” or as search for newness.”

Sandy Grande [Professor of Education, Director of the Center for the Critical Study of Race and Ethnicity, Connecticut College]

The Royal University of Bhutan has the Zhib’ Tshol, a document that guides research and innovation in the university. At the governmental level, there has been recent interest to bring the researching institutions/organizations of the nation together to develop a common approach and the possibility to institutionalize a National Research Council and develop a Gross National Happiness (GNH) based National Research Policy. Thus, Bhutan will be a country to watch and learn from regarding self-determination in how to approach research.

“So long as our texts, teachers and educational values glorify materialism, technological prowess, individualism, ambition, fame, career, and gain, we are lost….

“Bhutan is so proud that it was not colonized … But from Lhuentse to Thimphu and from Lunana to Gelephu, a much more insidious and far-reaching colonization has taken hold, as Bhutan’s imported education system transmits western values, goals and cultural norms that are entirely alien to Bhutan’s own esteemed wisdom traditions….

“There is nothing about our ‘ancient’ wisdom that keeps us stuck in the past. On the contrary, future generations can be taught to face the future with confidence through creative, practical, and forward-thinking solutions that are firmly grounded in our own unique forms of modernization.”

Dzongsar Jamyang Khentse Rinpoche

Bhutan Observer 2018

As our conversation at the Rimpung Lecture began to wind down its exploration of decolonizing research in Bhutan, we turned towards the question: Where Do We Go from Here? And How Do We Practice as Individuals?

How can we practice decolonizing as a deep personal praxis? Questioning and critique certainly, but also something a bit deeper. Leigh Patel offers us a pedagogy of pausing that involves intentionally suspending one’s own premises and projects. Deep pauses are useful, necessary, and productive interruptions to quiet down and unsettle the relentless march of educational research towards production of data, problems, and publication… A practice of pausing in order to reach beyond the typical tropes of our fields.

“Perhaps one of the most explicit decolonial moves we can make… is to sit still long enough to see clearly what we need to reach beyond.”

Leigh Patel, [PhD Associate Dean of Equity and Justice, University of Pittsburgh School of Education, USA]

At the end of the event, the room was charged with energy as a sense of unleashing creativity burst forth. Voices of the students in the audience begin pouring out on to the big screen on stage, speaking from their hearts through their cell phones, expressing their own next steps of decolonizing research in Bhutan. They wrote:

- We work together to strengthen ethics and develop right understanding of decolonized research. We spread the knowledge we have learned as we thirst for more.

- … think outside the box of traditional ways of research. Be mindful and hold clarity of purpose

- Localized learning

- We will look forward to research more

- To search inside

- Think on the subject critically henceforth as Bhutanese…

- Journey into self

- In order to move forward in a good way with re-search, we must realign ourselves with the heart, creating connections of care with the cultures and people we are working with.

- What are ways we can research “with” and not put the people/groups we are studying under a microscope?

- Baby steps. Start at home.

- From here we will go and research about places or things with respect and without discrimination.

- To go along with decolonizing research we need tremendous energy, altruistic mind, and lovely environment

- From here we can touch the untouched world

- A definition of what “research” is needs to be the first step. To use a biological metaphor we need to be careful not to use research as a tool that infects the specimen.

- Decolonizing the mind

- Need to think about the benefits of creating and generating knowledge for society.

- Research on the familiar which is not familiar to us

- Arouse your curiously and conduct research of your own locality.

- Involve the voices of people we are researching. Continue the conversation about decolonization, not only in classroom settings, but in the field as well.

- Be true to what is required in context to where I am from

- Take interest in doing research on those critical topics that we ignored till now.

- From here I have got the idea about decolonizing research, so I will do research on places and things that are left unknown to the world

- I think need to do research and find more about our country

- Research decolonization of culture in Bhutan

- Begin research from ‘Home’ with great passion and care to begin decolonizing research.

- Deep into research…….

Any many more!

This conversation has set a buzz on the campus that is continuing to wake-up the depth and dynamic possibilities that live within the cultural heritage of the Bhutanese ……and its importance in authentic research models and application.